Essay #94: Maryann Wilkinson, Executive Director, The Scarab Club and former Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, Detroit Institute of Arts

March 11, 2018

By Vince Carducci, Sculpture Magazine

Lois Teicher’s Curved Form with Rectangle and Space (2000) is just what its title says—a gently bowed piece of sheet steel rising up 14 feet from the ground, painted pure white with a tall, narrow rectangular space cut out of it just to the right of center. Constructed of a seemingly simple abstract form, upon inspection the sculpture reveals the complex nature of individual perception as it responds to object and the spatial environment.

Curved Form with Rectangle and Space sits on a small garden plot surrounded by a circular walkway. It is sited next to the modest Cotswold-style red brick building of the century-old artist’s association, the Scarab Club, and across the street from the recently completed Michael Graves plan for the expanded Detroit Institute of Arts. Walking around the sculpture, the space of the work’s title frames an inner-city panorama that moves from the grandeur (some might say pretension) of the DIA’s white marble-clad exterior to the banality of a parking lot that serves visitors to several nearby cultural institutions. Each view provides an opportunity to consider questions of the civic ideal and one’s place within the built environment. The potential for art to be the channel through which private thoughts enter the public domain has been a major theme of Teicher’s work from the beginning. A retrospective of the artist’s career in spring 2008 at the Saginaw Art Museum in Michigan was an occasion for taking stock of her evolution.

Teicher says her nearly three decades as an artist have been about the process of discovering her own artistic language.(1) Teicher entered art school as an adult in the mid-1970s in Detroit after having raised three children; she found herself negotiating imperatives of the time and place. On the one hand was the broad cultural current of second-wave feminism and on the other the more local concerns of a then solidifying “Detroit” canon that came to be known as the Cass Corridor style. Teicher’s development can be seen as a kind of personal and aesthetic “coming out.”

Celebration of Women (1979) is a sculptural environment consisting of a rough-finished lathwork wall in front of which stand upright and horizontal wooden elements that alternately read like the parts of an easel, a stick figure behind a table or countertop (or perhaps an ironing board?), or a cross. The piece pays homage to generations of female predecessors whose socially defined positions (not to mention the artist’s own personal experience) were sources of both creative enterprise and just as often restrictive burden. Constructed from recycled materials, the piece also engages the prevailing practice at the time in Detroit art of incorporating castoffs into assemblages reflecting the city’s nascent postindustrial environment.

The Cass Corridor aesthetic found expression in other early works. Vehicle Series (1980) resembles a post-Apocalyptic soapbox derby car. With its mismatched wheels and scrap-wood body rudely held together by found hardware and painted slapdash in institutional dark green, the piece could have been cobbled together from the ruins of an abandoned workshop. And indeed, the tinker (or bricoleur as postmodernists would have it) is one of the most pervasive tropes of the “Detroit” artist ideal-type. The piece also has something of an autobiographical component, recalling Teicher’s childhood practice of disassembling and reassembling her bicycle and making things from materials found in the field next to her family’s home.

Tilting more toward the mandate of gender identity are mixed-medium works such as Drawing with Red Strap (1983-84), a Styrofoam cutout medallion worked with modeling paste and a drawing glued on top, designed for wearing over the artist’s midsection during performances. Rendered in images of undulating folds and serrated contours, Drawing with Red Strap can be read as an iconographic manifestation of the vagina dentata. (Teicher describes herself as being “a raging feminist” in those years.)

Even in these early works, however, elements of the refined lexicon for which Teicher has come to be known were beginning to emerge. I Feel Like a Choreographer (1981) bridges diverging impulses and sets the stage for Teicher’s later work. The piece comprises five green wooden boxes whose front-facing openings are covered in wire screen. Each box stands upright on casters, enabling the components to be arranged to suit the space where the work is presented. (At the Saginaw museum, the boxes were lined up in a row along a single wall, minding their place as “good” works of art as installation conventions would prescribe.) The piece is more oblique than either the overtly feminist or Cass Corridor-influenced works, leaving interpretation in the hands of the viewer.

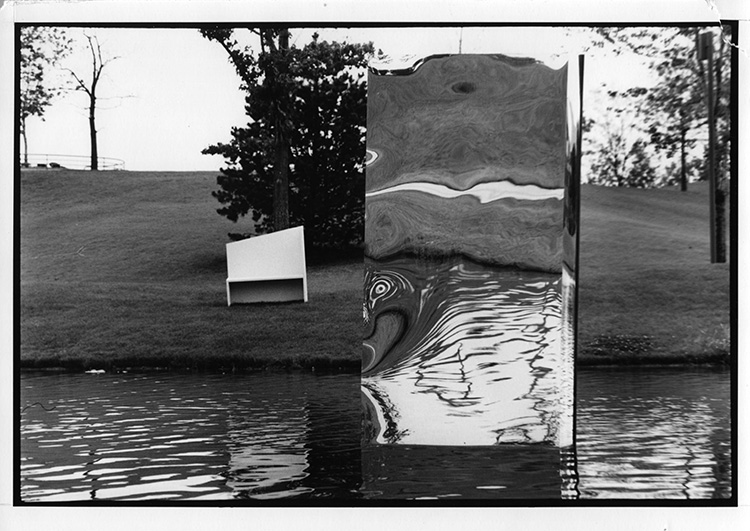

Teicher’s mature asthetic became clearly articulated in Observer/Observed (1986), which Observer/Observed was created for a temporary installation of outdoor sculptures in Chene Park, on the banks of the Detroit River near downtown. The installation featured four mirror-clad monoliths placed in the center of a small pond. Minimalist-inspired seating was arranged around the edges of the water, setting up situations for seeing and being seen, both by oneself and by others. Observer/Observed embodied what phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty, in his book The Visible and the Invisible, terms “chiasm”—the threshold between subjectivity and objectivity and the reciprocity (or “reversibility” as he calls it) that connects the two, the existential condition of being-in-the-world under which one experiences literally in the flesh the reality of self and otherness. Exposing the physical and metaphysical parameters of the field of being is one of art’s primary functions according to Merleau-Ponty, bringing together material form and expressive content in a made thing that communicates a relationship to the world in a unique way.

Teicher’s mature work –especially the public sculpture that has preoccupied her for the last decade – has continued to explore the geometric forms and simple palette of Observer/Observed, along with questions of creator and audience. Teicher is one of the most prolific public sculptors working in Michigan, and she is deeply committed to the idea of art as a public thing, something meant to engage viewers of all kinds not just the privileged few.

Her first major public commission in 1996 for Bishop International Airport in Flint, Michigan, established a pattern of distilling an essential visual language to communicate with broad audiences. Paper Airplane Series with Deep Groove (1996) is simple enough. It consists of three sheets of steel folded and painted to look like paper airplanes and placed throughout the airport as if having just landed after being tossed by some giant kid. The largest sits on the ground of the main concourse. It is painted white with light blue lines like ruled loose-leaf paper and even has binder holes punched into the tail edge. The casual whimsy of the piece belies its 3600-pound weight. Another plane is painted yellow to mimic the signage on a canopy above the main entrance and a smaller blue one teeters off the edge of a ledge.

Metaphor (2006), was commissioned by the State of Michigan Mass Transit Authority for its training center in Grand Blanc, just south of Flint. It uses images taken from traffic signs found in everyday experience. The forms are stylized and integrated into a dynamic composition that presents an optimistic view of the possibilities of education in the public interest.

All along, Teicher has maintained a studio practice and completed numerous private commissions in addition to public work. Wedge with Wedge with Wedge (1995) is an excellent example of Teicher’s exploration of pure sculptural form. Fabricated of welded aluminum painted a velvety soft black, the sculpture stands seven feet tall and leans against the wall. The first wedge in the title refers to the groove cut into the plane facing forward, which is wider at the top and narrows to a point as it nears the base. The second wedge refers to the sculpture’s overall mass, which tapers in depth from wider at the base to narrower at the top. The third is the negative space created by the sculpture leaning against the wall. With an economy of means, sculpture’s essence as spatial container and kinetic volume is revealed.

Teicher has executed numerous works that investigate the ostensible dichotomy of form and function. Half and Half Table (1996) is actually two narrow triangles that sit side-by-side to make up the rectangular shape of the tabletop. One half is about form as enclosure of space and the other about form as figure.

Although it might not seem obvious from her mature work, Teicher remains an unabashed feminist. It should go without saying (though it too often doesn’t) that in an equitable world the work would be all that matters. Second-wave feminists used to say that the personal is political. For Teicher, it is aesthetic, too.

- All references are taken from personal communication with the artist, published artist’s statements, or the documentary video Lois Teicher: The Journey (2008).

Vince Carducci has written for many publications, including Artforum, Art in America, Eye, and Metro Times. He teaches in the Liberal Arts Department at College for Creative Studies in Detroit.